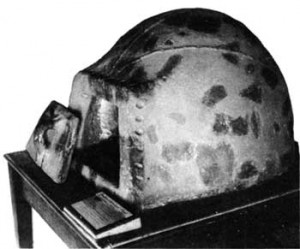

When Sidney Strickland excavated the Howland House in 1938, he noted the lack of an oven and posited that Elizabeth Howland must have baked her bread on the floor of the hearth. Unknown to Strickland, a single fragment of a North Devon domed bread oven had been recovered. This oven fragment, measuring approximately 15 cm long by 10 cm wide by 3.7 cm thick (6″ x 4″ x 1 1/2″), was identified by Malcolm Watkins in the late 1950s. Watkins reported on the fragment in his work North Devon pottery and its Export to America in the 17th Century which was published in 1960. Watkins compared the Howland sherd with pieces from Virginia and to a whole oven obtained by the Smithsonian, and found that they were identical in composition and style.

Ovens such as these have been recovered from sites in the Chesapeake and are known to have been shipped to Virginia and Maryland (Grant 1983: 120; Watkins 1960). They were produced in North Devon, England from the sixteenth century until at least 1890 (Watkins 1960: 31). The form of these ovens, a roughly oval beehive shape in a variety of sizes with a trapezoidal framed opening onto which a wooden or pottery door was fitted, remained unchanged for the entire period. These ovens were made by producing molded slabs of clay which were then draped over a mold form. These draped sections were carefully joined, thus creating a vessel with seams that were either tooled or thumb-impressed to provide reinforcement (Watkins 1960: 31).

During the 1950s excavations in Jamestown, Virginia, over 200 fragments of one of these ovens were found. The oven was described by Watkins as being “One wholly reconstructed oven at Jamestown. Made in sections on drape molds: base, two sides, two halves of top, opening frame, and door. Side and top sections are joined with seams, reinforced by finger impressions, meeting at top of trapezoidal opening. The opening was molded separately and joined with thumb-impressed reinforcements. A flat door with heavy vertical handle, round in section, fits snugly into opening. Thickness varies from 3/4″ to 1 1/2″. Unglazed, although smears of glaze dripped during the firing indicate that the oven was fired with glazed utensils stacked above it.” (Watkins 1960: 51).

The Jamestown oven was found in a ditch near the site of the May-Hartwell House and was probably used between 1650 and 1690. It has been reported (Watkins 1960) that an intact oven was identified in a standing house in the John Bowne House in Flushing, Long Island. The Bowne House reports that this is in fact not the case and that they do not have a clome oven but merely a standard brick oven.

These ovens appear to have been commonly added onto hearths, but they could also be free standing, as can be seen in an illustration of the French Huguenot Fort Caroline bread oven (1583) or could be placed on a cart ( Ulrich von Richental’s Concilium zu Constancz, printed at Augsburg in 1483). A few wealthier New England households also were noted as having bake houses associated with them. For example, John Barnes, a Plymouth merchant, was noted in 1671 as having a bake house within which was inventoried 1 Iron pott 2 tubbs 1 paile 1 old hogshed 2 old barrell and a halfe bushe amounting to a grand total of one pound. Edward Winslow was noted as having a “backhouse” at his house in Plymouth, which may either indicate that he had an privy, a storage building behind the house, or could be a misreading of the word bake house. I have never seen the original deed so I can not say for sure if the word is bake house or back house.

“[7th March 1645] Mr Edward Winslow doth acknowledg That for and in consideracon of the sum of thirty eight pounds allowed upon the said account in payment to Mr John Beauchamp Hath freely and absolutely bargained and sold unto Mr Edmond ffreeman All that his house scittuate in Plymouth wth the garden Backhouse doores locks bolts Wainscote glasse and Wainscote bedstead in the parlor wth the truckle bed a chaire in the study and all the shelves as now the are in eich roome wth yeard roomth and fences about the same and all & every their apprtenc…unto the said Edmond ffreeman his heires and Assignes for ever…”

A bakehouse would be another location where the ovens could be set up.

It is not known where the oven was used in John and Elizabeth Howland’s house. The fragment bears a catalog number but this number corresponds to a location on the other side of the house away from the hearth. This means that the oven may have been separate from the hearth or that pieces of the oven were shifted about when the house burned.

Today, these type of ovens are referred to as clome ovens. There is even a wikipedia page for them: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clome_oven.

Dr. Pococke, in 1730, noted that in Devonshire and Cornwall “they makke great use here of Cloume ovens, which are of earthen ware of several sizes, like an oven, and being heated they stop’em up and cover’em over with embers to keep in the heat.” (Watkins 1960: 31).

Paula Marcoux, an authority on 17th century baking (http://www.themagnificentleaven.com/About.html) believes that clome ovens were common in early houses possibly right from the start of the colony. It may be time for Plimoth Plantation to have ovens in their houses instead of the communal ones and for early depictions of colonial houses to include these as features of their hearths.

References

Bailey, Worth

1937 A Jamestown Baking Oven of the Seventeenth Century. William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. Series 2, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 496-500.

Bowne House: A Shrine to Religious Freedom, Flushing, New York. Pamphlet of the Bowne House Historical Society.

Cotter, John and J. Paul Hudson

2005 The Project Gutenberg EBook of New Discoveries at Jamestown

Grant, Allison

1983 North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century. The University of Exeter, Exeter, England.

Watkins, C. Malcolm

1960 North Devon pottery and its Export to America in the 17th Century. Bulletin 225, United States National Museum, Washington, D.C.

Comments are closed.