September 20, 1937

Proceeding with the excavations from this point, it required several days before we could clear the north wall and later on the foundations of the west wall. The latter proved the most difficult task of all because this west wall was in effect the chimney which had been built almost entirely of stone laid up with clay, the only form of mortar then at hand. A great mass of stone had to be sifted and moved in order to lay bare the form of the fire-place and hearth.

As the excavation of the hearth proceeded we encountered a large piece of metal, still unidentified. his metal is badly corroded, in fact it is a wonder that it survived at all, buried in clay which holds moisture at all times. It was thought to have been the top of a strong box or a piece of armor. The dimensions of this sheet of iron are 111/2″ x 151/2″ and its surface seems to have been covered with rivets. This object was located in the northerly end of the fire-place and great care was taken to preserve it intact. Working about to the south, before it was finally released, we found a second spoon. This spoon while not as perfect as the first, is still in very good state of preservation, lacking only the finial at the top of the handle.

Sept. 25th

11:00 a.m. C.R. Strickland working with Bert White found a piece of iron with a clasp Hinge 151/4″ x 111/4″ probably the lid of a strong-box. Great care taking care of this, which was removed finally at 3 p.m.

Sept. 27th 10:30 a.m.

C.R. Strickland finally has entire hearth of fireplace cleared out. There are stones missing from under fire hearth 2′ in from the south end. The pit is full of ash, charcoal and red clay. A stone of soft granite, which was lying in front of the outer hearth just fits in approximately half of this opening. The iron box lid was found right next to this hole. (Sidney Strickland excavation notes for the C-3 John Howland Site)

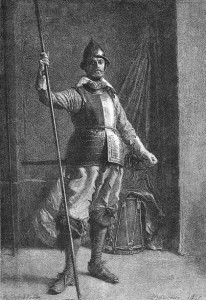

What the excavators found and so carefully recovered, was not a strongbox lid (which would have supported the local story that treasure was buried at the site), but was something more exciting- a tasset from a piece of armor. Pikeman’s armor in fact. The first of two known pieces of armor from Plymouth Colony. Alexander Young once mused that “One of their corslets would be a far more precious relic than a cuirass from the field of Waterloo.” (Young 1864: 134). While not a corslet, I believe that the tasset from the Howland site would satisfy Young’s desire.

Armor was a prerequisite for seventeenth century settlement in the New World, just as it was a crucial component of European military warfare. It protected against edge weapons as well as against musket balls, and in the case of the New World, against arrows. By the 1620s, previous English experience in Virginia had shown potential colonists that full or even half suits of armor were not needed or desirable for the New World colonization experience. A survey of probate inventories from Plymouth Colony, shown below and compiled by PARP, shows that headpieces (helmets) and corsletts (breast plates) were the most common items to be found in the inventories.

-

Armor 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s Armour 1 2 1 4 Head Piece 1 3 4 Old Head Piece 1 1 Cosett (corslett) 3 4 7 Buff Coat 1 1 2

Mourt’s Relation, a chronicle of the colonist’s first year in Plymouth believed to have been authored by William Bradford and Edward Winslow, records that armor was worn by the first men who explored Cape Cod in November of 1620 “… sixteene men were set out with every man his Musket, Sword, and Corslet, under the conduct of Captaine Miles Standish…” (Young 1864: 125). The armor proved effective against thorns and brush that colonists encountered on Cape Cod “…which tore our very armor in pieces” (Young 1864: 128). But the armor could prove a hinderance, limiting movement and fortunately for the Natives on Cape Cod, the ability to carry the Nauset Native’s maize that the colonists “discovered”. The colonists could only carry some of it and “The rest [of the maize] we buried again; for we were so laden with armor that we could carry no more.” (Young 1864: 134). Armor only works to provide protection from musket balls and arrows if the owner is wearing it, as the colonists foud out when, early one November morning, the Natives, possibly the owners of the “discovered” maize, taught them.

“About five o’clock in the morning we began to be stirring; and two or three, which doubted whether their pieces would go off or no, made trial of them and shot them off, but thought nothing at all. After prayer we prepared ourselves for breakfast, and for a journey ; and it being now the twilight in the morning, it was thought meet to carry the things down to the shallop. Some said it was not best to carry the armor down. Others said, they would be readier. Two or three said, they would not carry theirs till they went themselves, but mistrusting nothing at all. As it fell out, the water not being high enough, they laid the things down upon the shore, and came up to breakfast. Anon, all upon a sudden, we heard a great and strange cry, which we knew to be the same voices, though they varied their notes. One of our company, being abroad, came running in, and cried, ” They are men ! Indians! Indians! ” and withal their arrows came flying amongst us. Our men ran out with all speed to recover their arms; as by the good providence of God they did. In the mean time, Captain Miles Standish, having a snaphance ready, made a shot” (Young 1864: 156).

Possibly, the potential effectiveness of the armor to protect the wearer from arrows, was not lost on the Natives. When the colonists had their first meeting with the Pokonoket sachem Massasoit, “Our messenger made a speech unto him, that King James saluted him with words of love and peace, and did accept of him as his friend and ally; and that our governor desired to see him and to truck with him, and to confirm a peace with him, as his next neighbour. He liked well of the speech, and heard it attentively, though the interpreters did not well express it. After he had eaten and drunk himself, and given the rest to his company, he looked upon our messenger’s sword and armor, which he had on, with intimation of his desire to buy it; but, on the other side, our messenger showed his unwillingness to part with it.” (Young 1864:192).

The Plymouth colonists arrived with a specific military discipline in mind, one which was enacted by Captain Myles Standish. While their military establishment was likely implemented much earlier, in 1643 it was formerly recorded:

Establishment Of A Millitary Company Aug. 29, 1643.

The Court hath allowed & established a military discipline to be erected and mayntained by the Towns of Plimouth Duxborrow and Marshfield and have also heard their orders and established them— viz—

Orders.

1. That the exercise be alwayes begun and ended with prayer.

2. That there be one procured to preach them a sermon once a yeare, viz at the eleccon of their officers and the first to begin in Septr next.

3. That none shalbe received into this Millitary Company but such as are of honest and good report & freemen not servants, and shalbe well approved by the Officers and the whole Company or the major part.

4. That every person after they have recorded their names in the Millitary List shall from tyme to tyme be subject to the Comaunds and Orders of the Officers of this Millitary Company in their places respectively.

5. That every delinquent shalbe punished at the discretion of the Officers and the Millitary Company or the major part thereof according to the order of Millitary discipline & nature of the offence.

6. That all talking and not keepeing sylence during the time of the exercise jereing quarrelling fighting depring collers wthout lycence or dismission &c or any other misdemeanor, (so adjudged to be by the Officers and the Company or the majr pt thereof) to be accounted misdemeanors to be punished as aforesaid.

7. That every man that shalbe absent (except he be sick or some extrordinary occation or hand of God upon him) shall pay for every such default II*- And if he refuse to pay it upon demaund or within one month after then to appear before the Company and be distrayned for it and put out of the list.

8. That if any man shall (upon the dayes appoynted) come wthout his armes or wth defective armes shall forfaite for every trayneing day as followeth—

For want of a musket or a peece approved every time – – 6 shillings

For want of a sword —— 6 shillings

For want of a vest – – – – – — – 6 shillings

For want of bandelires ——- 6 shillings

Six months tyme given to prvide in.

9. That every man that hath entred himself upon the military list and hath not sufficient armes & doth not or will not prcure them wthin six months next ensuing his name to be put out of the list.

10. That there be but sixteene pikes in the whole company (or at the most for the third pt) viz—8 for Plimouth 6 for Duxborrow and 2 for Marshfield

11. That all that are or shalbe elected chiefe Officers in this Millitary Company shall be so titled and forever afterwards be so reputed except he obtayne a higher place.

12. That every man entred into the Millitary list shall pay VIrf the quarter to the use of the Company.

13. That when any of this Millitary Company shall dye or depart this life the company upon warneing shall come together with their armes and inter his corpes as a souldier and according to his place and quallytye.

14. That all that shalbe admitted into this Millitary Company shall first take the oath of fydellyty if they have not taken it already or els be not admitted.

15. That all postures of pike and musket, motions rankes and files &c messengers skirmishes seiges batteries watches sentinells &c bee alwayes prformed according to true millitary discipline.

16. That all that will enter themselves upon this Company shalbe propounded one day received the next day if they be approved.

Obviously, pike companies formed at least a part of the Plymouth Colony militia, but possibly only a small part as the record states that there will be BUT 16 pikes in the whole company and that there was no fine for forgettingto bring your pike to drill.

It is interesting to note that on the first exploring mission on Cape Cod, 16 men were equipped with armor, and the 1643 muster identifies 16 pikemen. The armor worn by the first 16 explorers may have been public/ colony owned armor which was subsequently used for the pike company. The Massachusetts Bay Colony left London with plate armor for 60 pikemen in their stores which had been purchased from Thomas Stevens of London. The March 6, 1628 purchase agreement between Stevens and the Colony stated thus:

“Agreement with Thomas Stevens, in Buttolph Lane for 20 armes, viz, corselet, breat, back, culet, gorgett, tases & head piece, all varnished and black. 17s each except 4 with closed helmets, these 24 s each.” (Peterson 2000:142).

Meaning you could buy a set of pikeman’s armor for 17 shillings. It is unknown if this is a wholesale or retail cost.

Sidney Strickland recovered a piece of armor, presumably John Howland’s, from the excavation of John and Elizabeth Howland’s hearth. The piece is what is termed a tasset which is part of a two-piece apron that hung below the breastplate (aka the corslett), and protected the upper legs. The tasset was a componet of the type of armor that pikemen wore. Pikemen were obviously the men who weilded the pikes in the militia.

The pike is a pole arm that varies in length from three to six meters (10-20 feet) (the full pike) or, for a half pike, 10 feet or less. The pole of the pike was made of ash, a strong flexible wood, with a head made of iron. On either side of the head, langets (metal strips) were affixed. The langets made it more difficult for mounted cavalry to slice off the heads with swords. Pikes were used as passive defensive weapons by arranging them in a hedgehog formation with the butt firmly planted against the foot and shaft tilted at a 45° angle towards the oncoming enemy. Pikes also served as aggressive weapons where the pikemen could position themselves to present a moving wall of pike heads that would be effective protection for the infantry against cavalry attacks. Unfortunately, as the pike mass consisted of men all facing the same direction, it was difficult for them to turn and maneuver against an enemy attacking their flanks or rear. Single pikemen from opposing forces could also duel against each other in single combat. Pike troops were most effective at rolling over an enemy before the enemy had a chance to out flank them. This made them potentially effective against attacks by Native warriors, if they were able to advance on attacking warriors, they could in theory rout them from their position and potentially gain strategic locations. They could also be used effectively to drive an enemy away from a fortification. Unfortunately, if the drive disintegrated into a close quarter meelee, the pikes were useless. Pikemen carried edge weapons such as daggers and swords, which would be used for hand to hand combat when the pike was rendered useless.

The armor worn by the pikeman most commonly consisted of a comb-cap (aka pikeman’s pot) helmet that offered protection against cavalry blows and musket shots to the head. The cuirass, was the set of torso armor, the backplate and the corslett that could be worn on top of a buff coat (a thick leather coat that could stop pistol shot and arrows) or possibly a padded/ quilted coat. The two halves of the cuirass were attached together by leather shoulder straps bearing iron plates for protection, and a narrow leather waist belt. Tassets were attached to the lower end of the corslett. These came in a left and a right pair, with the right overlapping the left like a coat. in Earlier examples, each lame, the nine plates that overlap to make the tasset, were individual, being attached together by rivets and leather straps, making the hole tasset flexible like a lobster tail. Later century tassets were forged as one piece, often retaining pseudo-lames with rivets that now were merely decorative. The tassets were attached to the corslett by means or two to three hooks on each tasset which locked via corresponding eyes on the corslett. The entire armor set weighed between 45 and 60 pounds.

Pikemen armor may have continued to see use though. With the discard of the tassets, the corslett and backplate would provide an effective bullet-proof shell. The protection provided against Native arrows was likely one of the reasons why corsletts appear frequently in the probate inventories. The widespread adoption of the flintlock musket rendered pikemen useless in battle. The pike appears to have been abandoned in New England by the late seventeenth century, especially after King Philip’s War. During this conflict, the English were faced with an enemy that fought with guerrilla warfare tactics, making companies of pikemen nothing more than large, slow moving targets that could easily be outflanked. The General Court in Massachusetts Bay in 1675 ruled that ” Whereas it is found by experience that troopers & pikemen are of little use in the present warr wth the Indians…all pikemen are hereby required…to furnish themselves wth fire armes…” (Peterson 2000:99). The prominence of the musket as the main weapon of war and the relative elimination of the Native threat in Plymouth Colony, led to the end of armor being seen as a necessity for the soldier. Armor, specifically corsletts, continued to be used into the eighteenth century.

It is interesting to note that on the first exploring mission on Cape Cod, 16 men were equipped with armor, and the 1643 muster identifies 16 pikemen. The armor worn by the first 16 explorers may have been public/ colony owned armor which was subsequently used for the pike company. The Massachusetts Bay Colony left London with plate armor for 60 pikemen in their stores which had been purchased from Thomas Stevens of London. The March 6, 1628 purchase agreement between Stevens and the Colony stated thus:

“Agreement with Thomas Stevens, in Buttolph Lane for 20 armes, viz, corselet, breat, back, culet, gorgett, tases & head piece, all varnished and black. 17s each except 4 with closed helmets, these 24 s each.” (Peterson 2000:142).

Meaning you could buy a set of pikeman’s armor for 17 shillings. It is unknown if this is a wholesale or retail cost.

The tasset from the Howland site is of the single-pieces, pseudo-lame design. This design became popular by the time of the Pilgrim’s colonization. No pieces of of this type of tasset have been recovered from Jamestown in Virginia (1607), but several elements from a Massachusetts Bay colonist’s (1630) pikeman’s suit bearing the same type of tasset do survive. One lame from a separate lame tasset was recovered from the John Alden site in Duxbury when the site was excavated by Roland Robbins. The Howland tasset is a right side tasset that bears a circular designs made from rivets, a common decoration on tassets. It measures 36 cm wide at the top, at 14 cm down from the top it measures 38 cm and is 39.5 cm wide at the bottom, the whole being 29 cm tall. The first four pseudo-lames are 3.2 cm wide while th last five are 3.7 cm wide. The hinges are 12.4 cm long and 3.2 cm wide. Its presence in the hearth may indicate that it was being used either as a fireback or it may have been used to cover the hole in the hearth that it lay near, possibly a hole that once contained…treasure! (Just kidding).

Some good Websites that discuss Pikes, Pikemen, and Pike Drills

Royal Armouries: Pikemen’s Armour

Cardiff Rose Swordsmen Guild Costume Guidelines – Pikemen

Virginia Department of Historic Resources Archaeological Collections

Comments are closed.