Paleoecological Reconstruction

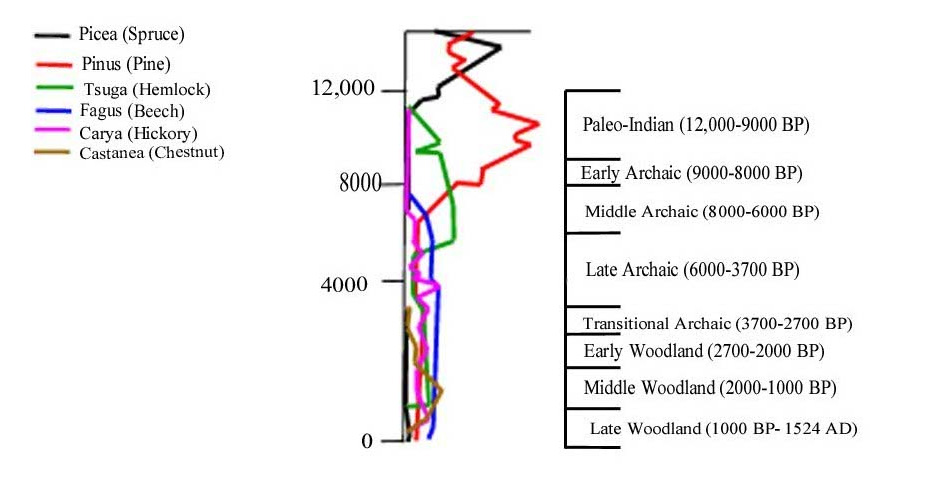

Deevey (1939) carried out the pollen study that established the base map for interpreting post glacial environmental change in New England. Basing his conclusions on pollen cores carried out in Connecticut, he identified six phases of environmental change in post-glacial New England:

Phase 1- cold glacial conditions 5-10°C colder than present. This period ended by ~14,600 BP when the temperature rose rapidly. during the cold period, tundra like conditions existed in New England (identified by palynologists as the T Zone), with abundant cold tolerant sedges and other herbs by 14,000 BP and a low frequency of arboreal pollen except in some areas that showed high spikes in Spruce pollen. This indicates that there was a mixture of open tundra and wooded patches across the landscape (Webb et al. 2004: 1302). Spruce came to dominate the assemblages by 14, 600 BP (A Zone) with a concurrent increase in pine pollen as well as traces of oak, ash, beech and hornbeam.

Phase 2-a possible late advance of glaciers (warming continued to ~12,900 BP when the Younger Dryas chronozone caused the coldest conditions since 14,600 BP, this period lasted until ~11,600 BP). This temperature decrease reversed the advancement of the spruce woodlands and overall caused a decided shift to an almost total spruce dominated pollen record.

Phase 3- cool, dry conditions (at the end of the Younger Dryas temperatures rose rapidly and remained similar to modern conditions until after 8000 BP). Pine began to dominate the pollen spectra with rising temperatures at the end of the YDC with a concurrent spruce decline to near zero (B Zone). Between 11,600 and 9000 BP, pine dominated the pollen spectra. Pines are not abundant when moisture levels are low, hence, good evidence of high moisture levels in this period (Webb et al. 2004: 1304). Maple and oaks also have similar preferences and their occurrence increased at this time as well.

Phase 4-warm, moist conditions (temperatures were warmer than modern times after 8000 BP based on a spike in the hemlock pollen profile at this point with a rise of 3-7°C between 8200-5400 BP) This was the beginning of the oak dominated assemblage (C1 Zone) which saw an increase in beech along with the hemlock and a decrease in pine. The inverse occurrence of these species indicates wetter and warmer conditions. There is also a noticeable absence of hickory and chestnut, species that have the highest temperature preferences and act as clear markers differentiating the early oak dominated assemblage from the later (Webb et al. 2004: 1304).

The later oak dominated assemblage (C2 Zone) shows an increase in hickory pollen, a species more tolerant of drier conditions than other species indicating temperatures at least as warm as today (Webb et al. 2004: 1304). The highest percentage of hickory pollen occurs after 5400 BP, a date that also marked the dramatic drop off of the hemlock pollen in the profiles. While researchers have found indications of pathogens possibly being partially responsible for the hemlock drop, hemlock is a moisture loving species while hickory tolerates drier conditions, marking this period as one that was drier than its predecessor (Webb et al. 2004: 1304).

Phase 5-warm dry conditions (temperatures remained high from 5400-3000 BP then declined) which exhibited an increase in dry tolerant pine species (Webb et al. 2004: 1305).

Phase 6-moist and/ or cooler than earlier conditions (after 3000 BP temperature decline, evident as an elevation in the hemlock and pine pollen) (Webb et al. 2004). The final oak dominated assemblage (C3 Zone) shows an increase in chestnut pollen. Chestnuts grow under a similar range in temperature to hickory but high pollen occurrences are indicative of dry conditions with higher moisture than that needed by species such as hickory (Webb et al. 2004: 1305). There is also a clear increase in hemlock occurrence at this time (another moisture loving species).

The pollen profile recovered from Pocksha marsh in Lakeville showed that during the earliest period (Zone 1 13-15,000 BP Deevey Phase 1), tundra conditions existed in this part of Massachusetts (Hoffman 1991a:148). Black and Jack pine species dominated the pollen spectra (63%) with birch being the next most abundant (14%) and other species (spruce, oak, alder, willow and ash) making a minor contribution during this period. Non-arboreal species, species that represent ground vegetation (grass, ragweed, asters, daisies, goldenrod, wormwood, goosefoot, meadow rue, buttercup, rose, currants, violets, and heath), were well represented. The presence of these species as well as traces of waterleaf, show that the area was open water with a shoreline that was not far away from the sample core location (Hoffman 1991a: 148). Zone 1 showed that while tundra conditions existed in the area, the northward advancing jack pine forest was getting closer by this period and the marsh was already forming.

Zone 2 (12,000-12,500 BP Deevey Phase 2) showed more spruce and generally more organics existing in the system by this point. Jack pine coexisted with the earlier spruce and larger birch species also existed (Hoffman 1991a: 152). There also was a drop in non-arboreal species, indicating the establishment of woodlands (chiefly spruce) versus the open meadows present in the earlier zone.

Zone 3 (10,500-11,000 BP Deevey Phase 3) showed a peak in birch pollen, a dramatic increase in white pine and a sharp decline in spruce (Hoffman 1991a: 153). These trends, especially the increase in white pine, a temperate zone species, show that conditions were warmer here at the end of the Pleistocene. There were also co-occurring increases in elm, ash and hemlock species pollen, and at the top of the zone, an increase in oak and red maple pollen (Hoffman 1991: 153).

Above Zone 3, Zone 4 (10,000 BP to present Deevey Phases 4-6) characterized as the New England Oak Period, showed the appearance of beech by 8,000 BP (Deevey Phase 4), an increase in hickory by 5,000 BP (Deevey Phases 4-5) and the establishment of chestnut by 2,000 BP (Deevey Phase 6) (Hoffman 1991a: 154). The appearance and establishment of these mast species may have had important consequences to seasonal foraging and collecting rounds of Native people living in the area by providing predictable seasonal supplied of high fat mast species collected, processed and stored for winter and spring use. Three sub-zones make up the New England Oak Period:

Oak-Hemlock zone (10,000-4,700 BP) (Deevey Phase 4)

Oak-Hickory zone (4,700-2,000 BP) (Deevey Phase 5)

Oak-Chestnut zone (2,000-present) (Deevey Phase 6)

Co-occurring with these species were holly and later gum, grape and new birch species also appeared in this zone (Hoffman 1991a: 156). An increase in ragweed occurred at the same time as the increase in beech (ca. 8,000 BP) interpreted as a mid-Holocene dry period (hypsithermal) characterized by dune formation, a declining water table and an expansion of weeds adapted to (Hoffman 1991a: 157). Evidence of this hypsithermal period appeared to be lacking in the Pocksha marsh core, leading Hoffman to interpret that this dry period, first identified in pollen cores taken during the Public Archaeology Laboratory’s work along Route 495, could be a local occurrence and was not so widespread as previously interpreted (Hoffman 1991a: 158). It also could be possible that Pocksha Marsh was not as dramatically affected as other areas. Also apparent in the soil profile was evidence of significant local environmental changes following the arrival of chestnuts (ca. 2,000 BP) (Hoffman 1991a: 160)

Shuman et al.’s 2004 findings supported the findings of Newby et al. (2000) who found that water levels at the Makepeace Swamp in Carver showed marked fluctuations after 15,000 BP. Theorizing that these water level changes correlated with temperature change, species abundance, and by extension, moisture levels, they found a marked decrease by up to one and one half meters between 10,800 and 9700 BP and a rise of approximately two meters around 8000 BP, changes that correspond with cold, dry conditions at the end of the YDC (Deevey Phase 2) and warmer moister conditions in Deevey’s Phase 3. Drier conditions occurred after this but by 3200 BP the water level had risen close to it highest possible level, which is the current level (Newby et al. 2000: 352).

Deevey’s conclusions are important to New England archaeology because he found that some plant taxa that are known to have been important to Native foodways in the Contact Period (chestnut, hickory, beech) expanded north only in the last few thousand years even though the summer temperatures exceeded modern values several millennia earlier than that. Shuman et al. (2004) make the convincing case moisture differences inhibited the northward spread of some species (Webb et al. 2004: 1298). The researchers based their findings on paleotemperature indicators and lake level estimates that show a combination of temperature and moisture balance over the last 15,000 that complements the vegetational history clear in the pollen record (Webb et al. 2004: 1300).

The vegetational history may show a positive correlation with the cultural occupation of many sites in southeastern Massachusetts (Figure). The first clearly recognizable occupation in the project area was

during the Middle Archaic period, a short-term encampment by people utilizing Neville and Stark projectile points, identified in the Lot 2 House impact area. This occupation was most probably focused on the wetlands to the immediate southwest of this impact area. At this time, drier conditions occurred and populations tended to camp near bodies of water such as swamps and wetlands. By the later part of the Late Archaic period and into the Transitional Archaic and Early Woodland periods (the second period of definitive occupation at the site), cooler, moister conditions prevailed and the distribution of hickory and, eventually by 2000 BP, chestnut forests, had spread into this area. The co-occurrence of more visible occupation, the rise in the use of soapstone and especially pottery, and the increase in mast forests are probably related. More mast that could be harvested for winter use (hickory and chestnut), new technology for processing the mast for long-term storage and possibly easier digestion (soapstone bowls and pottery), both could have led to the creation and use of base camps in the very Late Archaic into the early Woodland periods, from which collecting and hunting parties would have based themselves around. These early base camps eventually may have evolved into community centers (“villages”) once horticulture entered the diet of these people, possibly in the second half of the Middle Woodland Period. The Middle Woodland was also the period when chestnut pollen was very prevalent in the pollen spectra, which correlates well with the ethnographic data regarding the prominence of chestnuts in the Native diet during the Contact Period, a preference which appears to have had its roots in the Middle Woodland Period.